In Memory of my father, Obong (Major General)

Philip Efiong, Akangkang Ibiono Ibom

(November 18, 1925 - November 6, 2003)

Philip Efiong, Akangkang Ibiono Ibom

(November 18, 1925 - November 6, 2003)

|

| Major General Philip Efiong-Biafran Number two man |

In

Memory of my father, Obong (Major General)

Philip Efiong, Akangkang Ibiono Ibom

(November 18, 1925 - November 6, 2003)

Philip Efiong, Akangkang Ibiono Ibom

(November 18, 1925 - November 6, 2003)

May the soul of a great dad and

exceptional statesman

rest in perfect peace! By his son |

About Major General Philip Efiong

Obong (Major General) Philip Asuquo Efiong of

Ikot Akpan Obong in Utit Obio Clan of Ibiono Ibom Local Government Area of Akwa

Ibom State was born on 18 November 1925 in Aba, present Abia State,

Nigeria. His father, the late Eté John Efiong Essien, was a businessman while

his mother, the late Elizabeth Ekandem Efiong Essien, was a trader and farmer.

(The Efiong Essien family ended up in Ikot

Ekpene after Eté John moved his household from Aba to Ikot Ekpene in

1929. This was in a bid to avoid victimisation against his wife who had

participated in the legendary Eastern Women’s Revolution of that same year.)

The young Philip began his education at Saint

Anne’s Catholic Primary School, Ifuho in Ikot Ekpene, from where he obtained

his Standard Six Certificate, which, at the time, qualified him to be a pupil

teacher. He was posted to Nto Otong Midim, Abak after which he relocated to

Saint Thomas’ Teacher Training College, Ogoja and later the Seminary at

Saint Patrick’s College, Ikot Ansa, Calabar. He left the Seminary in 1944 and

moved on to Saint Augustine’s, Urua Inyang to study for his Higher Elementary

Certificate.

In 1945, the Philip left teaching entirely and

joined the Army (the West African Frontier Force), enlisting as a private

in Enugu. At the end of the Second World War, he was converted to a regular

soldier in the renamed Royal West African Frontier Force. Private Philip

Efiong was among the first batch of educated recruits posted to Zaria,

which was then the training depot for young enlisted soldiers. Part of his

training involved clerical instruction at the Clerical Training School in

Teshi, Ghana. On his return to Nigeria, he was posted to the Lagos Garrison

Office and promoted to the rank of Lance Corporal in 1947. He was subsequently

promoted Corporal in 1948 and Sergeant in 1949. Also in 1949, Sergeant Philip

Efiong was posted to Zaria to help set up the African Non-Commissioned Officers

School (ANCO) under the supervision of a British Warrant Officer II. While in

Zaria, he studied on his own, sat for and passed the Cambridge Overseas School

Certificate examination in 1953. He was then posted to the Orderly Room as the

recruiting Non-Commissioned Officer (NCO).

It was also around 1953 that the Intelligence

Quotient (IQ) test was introduced into the Army and Sergeant Philip Efiong’s

result in the test was used as a base for evaluating the new recruits. In 1954

he was promoted Sergeant Major and in 1955 was again sent to Teshi, this time

to the Regular Officers Special Training School. On his return, he was

recommended for training in Britain and subsequently trained at the Home

Countries Brigade, Canterbury, and Eaton Hall Officers Cadet Training

School in Chester and Trawnysfyld in Wales. At the passing out parade in

Chester in 1956, he was commissioned Second Lieutenant and later that year was

promoted Lieutenant.

In 1958 Lieutenant Philip Efiong went on to

do his post commissioning training in various parts of Britain, the Kings Own

Yorkshire Light Infantry in Düsseldorf in Germany, and the British Army of the

Rhine (BAOR) in West Germany. That same year he was promoted to

Captain. He served in various capacities.

In 1959 Captain Philip Efiong served in the

Cameroons with the peacekeeping force. As a Major in 1960, he also served in

peacekeeping operations under the United Nations as a Company Commander in the

Republic of Congo. He was later recalled from the Congo in 1961 and transferred

to the Nigerian Army Ordnance Corps. As follow-up to this transfer, he

proceeded to Britain to attend an ordnance course at the Royal Army Ordnance

Corps (RAOC) School in Blackdown near Aldershot in England. This course

led to his being awarded Associate Member of the British Institute of

Management (AMBIM). On completion of his ordnance training, he became the first

Nigerian Commander of the Ordnance Depot in Yaba, Lagos in 1962, and the

first Nigerian Director of Ordnance Services of the Nigerian Army in 1963,

the year he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel. This was the post and rank he

held when the first coup d'état took place on January 15 1966.

After the coup d'état of January 1966, Lieutenant

Colonel Philip Efiong was posted to Supreme Headquarters as Principal

Staff Officer to the late Major General J.T.U. Aguiyi-Ironsi. He was Acting

Chief of Staff Supreme Headquarters in May 1966 and in July 1966 was posted to

Kaduna as Deputy Brigade Commander under the late Lieutenant Colonel

Wellington Bassey. Following the countercoup of the same year, he managed to

escape from Kaduna to Lagos. In compliance with orders for all officers to

return to their regions of origin, he returned to the East where, in 1967,

the war broke out. For Obong Philip Efiong, this marked the beginning of the

end of 22 years of meritorious service in the Nigerian Army.

As a Biafran officer from 1967 to 1970, Obong

Philip Efiong served in various capacities as Chief of Logistics, Chief of

Staff, Commandant of the Militia, and Chief of General Staff.

In January 1970, Major General Philip

Efiong called for an end to the hostilities and voluntarily led a

delegation of surrender to General Gowon in Lagos.

Obong Philip Efiong received many honours in

his lifetime, most of them expressing tribute to his courage. It was for this

reason that the Ibiono Ibom Traditional Council of Chiefs conferred him with

the title of Akangkang Ibiono Ibom (the Sword of Ibiono Ibom) in 1995.

After battling occasional health problems, Obong Philip Efiong passed away on 6 November 2003, 12 days to his 78th birthday. He is survived by a wife, eight children, several grandchildren and a host of relatives.

|

| 1969, at parade to celebrate the Second Independence Anniversary of Biafra; General Efiong is fourth from left; General Ojukwu, Head of State, is fifth from left |

|

1970, initial meeting between both sides atthe end of the War; from left to right: General Efiong,Prof. Eni Njoku, Colonel Obasanjo |

|

1969, Major General Philip Efiong returning

from a visit to a refugee camp at Nto Edino in present Akwa Ibom State |

|

| End of the War; In the true spirit of African reconciliation, kola nut is shared; General Efiong, extreme right, takes a piece |

|

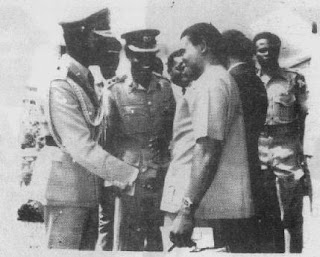

| Right, Lagos, 15 January 1970, General Efiong shakes hand with General Gowon after surrender |

|

| January 1970, preparing for meeting in Lagos at the end of the Civil War; second from left is General Efiong, third is Colonel O. Obasanjo |

@ @ @ @ @ @ @

About

Biafra

Several sociopolitical factors led to

the Nigeria-Biafra Civil War (1967-1970), including upheavals in Nigeria’s

Western Region and Middle Belt in the mid-1960s; the first military coup

carried out on January 15, 1966 to allegedly curb the deteriorating state of

corruption and conflict; a countercoup mostly led by northern officers who

perceived the first coup as ethnically biased; and the subsequent massacre of

eastern (mostly Ibo) officers, men, and women primarily in Lagos and northern

Nigeria. The ensuing forced relocation of thousands of easterners to the East

engendered tensions between the Governor of the Eastern Region,

Lieutenant-Colonel C. Odumegwu-Ojukwu and the new Head-of-State enthroned by

the countercoup, Lieutenant-Colonel Y. Gowon. The inability of both leaders to

reach an agreement on future administrative and military issues resulted in a

decision by the Eastern Region to secede from the rest of the country. In

response, the Nigerian military government launched a "police action"

to retake the secessionist territory and this escalated to a 31-month civil war

that officially began on July 6, 1967.

Aside from the huge advantage that the

federal side enjoyed in terms of regional size, it received tremendous support

in arms and other military supplies from the likes of Russia, Egypt, and

Britain, and also utilized tactics like the bombardment of civilian facilities,

the shooting down of relief planes, economic blockade, and the deliberate

destruction of agricultural land, which caused mass refugee problems and

starvation of the populace. It is estimated that two to three million people

died in the conflict, mostly through starvation and illness.

When the collapse of Biafra's

military was imminent, General Ojukwu fled to Côte d'Ivoire, after which his

Second-in-Command and Chief of General Staff, General Effiong, assumed

leadership of the young ailing nation on 8 January, 1970. On 12 January,

Effiong called for a ceasefire and an end to hostilities. Three days later, on

January 15, he led a Biafran delegation comprising civilian and military

officials to Lagos, then Nigeria’s capital, where, in a ceremony at Dodan

Barracks, he officially delivered the instrument of Biafra’s surrender to

General Y. Gowon.

For my family, the war began in Lagos after

the countercoup of July 1966. For security reasons, we relocated to another

section of Lagos where we were accommodated by the family of Colonel R.

Trimnell. We eventually escaped to Enugu where we were when the war commenced

in full. With each incursion of the enemy, we relocated to different towns.

From Enugu we moved to Ikot Ekpene and then to Umuahia. We fled Umuahia when it

was on the verge of falling into the hands of the enemy and ended up in

Ifakala, a rural town, where family friends accommodated us for several weeks

because we were homeless. From Ifakala we relocated to Owerri after Biafra

recaptured the town from the enemy. We were still in Owerri when the enemy’s

final onslaught took place, forcing us out of the town. About three days before

Biafra’s final collapse; me, my mother, two brothers and a cousin fled Biafra

in a seat-less cargo plane while my father stayed back to handle the young

nation’s final surrender.

Why we were sold to the

British for £865k in 1899

About

Biafra

Several sociopolitical factors led to

the Nigeria-Biafra Civil War (1967-1970), including upheavals in Nigeria’s

Western Region and Middle Belt in the mid-1960s; the first military coup

carried out on January 15, 1966 to allegedly curb the deteriorating state of

corruption and conflict; a countercoup mostly led by northern officers who

perceived the first coup as ethnically biased; and the subsequent massacre of

eastern (mostly Ibo) officers, men, and women primarily in Lagos and northern

Nigeria. The ensuing forced relocation of thousands of easterners to the East

engendered tensions between the Governor of the Eastern Region,

Lieutenant-Colonel C. Odumegwu-Ojukwu and the new Head-of-State enthroned by

the countercoup, Lieutenant-Colonel Y. Gowon. The inability of both leaders to

reach an agreement on future administrative and military issues resulted in a

decision by the Eastern Region to secede from the rest of the country. In

response, the Nigerian military government launched a "police action"

to retake the secessionist territory and this escalated to a 31-month civil war

that officially began on July 6, 1967.

Aside from the huge advantage that the

federal side enjoyed in terms of regional size, it received tremendous support

in arms and other military supplies from the likes of Russia, Egypt, and

Britain, and also utilized tactics like the bombardment of civilian facilities,

the shooting down of relief planes, economic blockade, and the deliberate

destruction of agricultural land, which caused mass refugee problems and

starvation of the populace. It is estimated that two to three million people

died in the conflict, mostly through starvation and illness.

When the collapse of Biafra's

military was imminent, General Ojukwu fled to Côte d'Ivoire, after which his

Second-in-Command and Chief of General Staff, General Effiong, assumed

leadership of the young ailing nation on 8 January, 1970. On 12 January,

Effiong called for a ceasefire and an end to hostilities. Three days later, on

January 15, he led a Biafran delegation comprising civilian and military

officials to Lagos, then Nigeria’s capital, where, in a ceremony at Dodan

Barracks, he officially delivered the instrument of Biafra’s surrender to

General Y. Gowon.

For my family, the war began in Lagos after

the countercoup of July 1966. For security reasons, we relocated to another

section of Lagos where we were accommodated by the family of Colonel R.

Trimnell. We eventually escaped to Enugu where we were when the war commenced

in full. With each incursion of the enemy, we relocated to different towns.

From Enugu we moved to Ikot Ekpene and then to Umuahia. We fled Umuahia when it

was on the verge of falling into the hands of the enemy and ended up in

Ifakala, a rural town, where family friends accommodated us for several weeks

because we were homeless. From Ifakala we relocated to Owerri after Biafra

recaptured the town from the enemy. We were still in Owerri when the enemy’s

final onslaught took place, forcing us out of the town. About three days before

Biafra’s final collapse; me, my mother, two brothers and a cousin fled Biafra

in a seat-less cargo plane while my father stayed back to handle the young

nation’s final surrender.

Why we were sold to the British for £865k in 1899

Why we were sold to the British for £865k in 1899

@ @ @ @ @ @ @

Alhaji Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, the

first prime minister of Nigeria, was assassinated during the January 1966

military coup.

@ @ @ @ @ @ @

|

Alhaji Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, the

first prime minister of Nigeria, was assassinated during the January 1966

military coup.

|

In the following address given eleven years before Nigerian independence, Nnamdi

Azikiwe calls for self-determination for the Ibo as they along with other

ethnic groups march toward an inevitably free Nigeria. This address was

delivered at the Ibo State Assembly held at Aba, Nigeria, on Saturday,

June 25, 1949.

It would appear that God has

specially created the Ibo people to suffer persecution and be victimized

because of their resolute will to live. Since suffering is the label of our

tribe, we can afford to be sacrificed for the ultimate redemption of the

children of Africa. Is it not fortunate that the Ibo are among the few remnants

of indigenous African nations who are still not spoliated by the artificial

niceties of Western materialism? Is it not historically significant that

throughout the glorious history of Africa, the Ibo is one of the select few to

have escaped the humiliation of a conqueror’s sword or to be a victim of a

Carthaginian treaty? Search through the records of African history and you will

fail to find an occasion when, in any pitched battle, any African nation has

either marched across Ibo territory or subjected the Ibo nation to a

humiliating conquest. Instead, there is record to show that the martial prowess

of the Ibo, at all stages of human history, has rivaled them not only to

survive persecution, but also to adapt themselves to the role thus thrust upon

them by history, of preserving all that is best and most noble in African

culture and tradition. Placed in this high estate, the Ibo cannot shirk the

responsibility conferred on it by its manifest destiny. Having undergone a

course of suffering the Ibo must therefore enter into its heritage by asserting

its birthright, without apologies.

Follow me in a kaleidoscopic study of the Ibo. Four million strong in

man-power! Our agricultural resources include economic and food crops which are

the bases of modern civilization, not to mention fruits and vegetables which

flourish in the tropics! Our mineral resources include coal, lignite, lead,

antimony, iron, diatomite, clay, oil, tin! Our forest products include timber

of economic value, including iroko and mahogany! Our fauna and flora are

marvels of the world! Our land is blessed by waterways of world renown,

including the River Niger, Imo River, Cross River! Our ports are among the best

known in the continent of Africa. Yet in spite of these natural advantages,

which illustrate without doubt the potential wealth of the Ibo, we are among

the least developed in Nigeria, economically, and we are so ostracized

socially, that we have become extraneous in the political institutions of

Nigeria.

I have not come here today in order to catalogue the disabilities which the Ibo

suffer, in spite of our potential wealth, in spite of our teeming man-power, in

spite of our vitality as an indigenous African people; suffice it to say that

it would enable you to appreciate the manifest destiny of the Ibo if I

enumerated some of the acts of discrimination against us as a people. Socially,

the British Press has not been sparing in describing us as ‘the most hated in

Nigeria’. In this unholy crusade, the Daily Mirror, The Times, The Economist, News

Review and the Daily Mail have been in the forefront. In the Nigerian Press,

you are living witnesses of what has happened in the last eighteen months, when

Lagos, Zaria and Calabar sections of the Nigerian Press were virtually

encouraged to provoke us to tendentious propaganda. It is needless for me to

tell you that today, both in England and in West Africa, the expression ‘Ibo’

has become a word of opprobrium.

Politically, you have seen with your own eyes how four million people were

disenfranchized by the British, for decades, because of our alleged

backwardness. We have never been represented on the Executive Council, and not

one Ibo town has had the franchise, despite the fact that our native political

institutions are essentially democratic—in fact, more democratic than any other

nation in Africa, in spite of our extreme individualism.

Economically, we have laboured under onerous taxation measures, without

receiving sufficient social amenities to justify them. We have been taxed

without representation, and our contributions in taxes have been used to

develop other areas, Out of proportion to the incidence of taxation in those

areas. It would seem that we are becoming a victim of economic annihilation

through a gradual but studied process. What are my reasons for cataloguing

these disabilities and interpreting them as calculated to emasculate us, and so

render us impotent to assert our right to life, liberty and the pursuit of

happiness?

I shall now

state the facts which should be well known to any honest student of Nigerian

history. On the social plane, it will be found that outside of Government

College at Umauhia, there is no other secondary school run by the British

Government in Nigeria in Ibo-land. There is not one secondary school for girls

run by the British Government in our part of the country. In the Northern and

Western Provinces, the contrary is the case. If a survey of the hospital

facilities in Ibo-land were made, embarrassing results might show some sort of

discrimination. Outside of Port Harcourt, fire protection is not provided in

any Ibo town. And yet we have been under the protection of Great Britain for

many decades!

On the economic plane, I cannot

sufficiently impress you because you are too familiar with the victimization

which is our fate. Look at our roads; how many of them are tarred, compared,

for example, with the roads in other parts of the country? Those of you who

have travelled to this assembly by road are witnesses of the corrugated and

utterly unworthy state of the roads which traverse Ibo-land, in spite of the

fact that four million Ibo people pay taxes in order, among others, to have

good roads. With roads must be considered the system of communications, water

and electricity supplies. How many of our towns, for example, have complete

postal, telegraph, telephone and wireless services, compared to towns in other

areas of Nigeria? How many have pipe-borne water supplies? How many have

electricity undertakings? Does not the Ibo tax-payer fulfill his civic duty?

Why, then, must he be a victim of studied official victimization?

I shall now

state the facts which should be well known to any honest student of Nigerian

history. On the social plane, it will be found that outside of Government

College at Umauhia, there is no other secondary school run by the British

Government in Nigeria in Ibo-land. There is not one secondary school for girls

run by the British Government in our part of the country. In the Northern and

Western Provinces, the contrary is the case. If a survey of the hospital

facilities in Ibo-land were made, embarrassing results might show some sort of

discrimination. Outside of Port Harcourt, fire protection is not provided in

any Ibo town. And yet we have been under the protection of Great Britain for

many decades!

On the economic plane, I cannot

sufficiently impress you because you are too familiar with the victimization

which is our fate. Look at our roads; how many of them are tarred, compared,

for example, with the roads in other parts of the country? Those of you who

have travelled to this assembly by road are witnesses of the corrugated and

utterly unworthy state of the roads which traverse Ibo-land, in spite of the

fact that four million Ibo people pay taxes in order, among others, to have

good roads. With roads must be considered the system of communications, water

and electricity supplies. How many of our towns, for example, have complete

postal, telegraph, telephone and wireless services, compared to towns in other

areas of Nigeria? How many have pipe-borne water supplies? How many have

electricity undertakings? Does not the Ibo tax-payer fulfill his civic duty?

Why, then, must he be a victim of studied official victimization?

Queen Elizabeth and her husband Prince Phillip pictured with Nigeria's first head of state Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe and HRH Obi Okosi, the Obi of Onitsha in the

The keynote in this address is self-determination for the Ibo. Let us establish

an Ibo State, based on linguistic and ethnic factors, enabling us to take our

place side by side with the other linguistic and ethnic groups which make up

Nigeria and the Cameroons. With the Hausa, Fulani, Kanuri, Yoruba, Ibibio

(Iboku), Angus (Bi-Rom), Tiv, Ijaw, Edo, Urhobo, ltsekiri, Nupe, Igalla, Ogaja,

Gwari, Duala, Bali and other nationalities asserting their right to

self-determination each as separate as the fingers, but united with others as a

part of the same hand, we can reclaim Nigeria and the Cameroons from this

degradation which it has pleased the forces of European imperialism to impose

upon us. Therefore, our meeting today is of momentous importance in the history

of the Ibo, in that opportunity has been presented to us to heed the call of a

despoiled race, to answer the summons to redeem a ravished continent, to rally

forces to the defence of a humiliated country, and to arouse national

consciousness in a demoralized but dynamic nation.

Sources:

Nnamdi Azikiwe, Zik: A Selection from the Speeches of Nnamdi Azikiwe,

Governor-General of the Federation of Nigeria formerly President of the

Nigerian Senate formerly Premier of the Eastern Region of Nigeria (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1961).

n

In the following address given eleven years before Nigerian independence, Nnamdi

Azikiwe calls for self-determination for the Ibo as they along with other

ethnic groups march toward an inevitably free Nigeria. This address was

delivered at the Ibo State Assembly held at Aba, Nigeria, on Saturday,

June 25, 1949.

Harbingers of a new day for the Ibo

nation, having selected me to preside over the deliberations of this assembly

of the Ibo nation, I am conscious of the fact that you have not done so because

of any extraordinary attributes in me. I realize that I am not the oldest among

you, nor the wisest, nor the wealthiest, nor the most experienced, nor the most

learned. I am therefore grateful to you for elevating me to this high pedestal.

The Ibo people have reached a

cross-road and it is for us to decide which is the right course to follow. We

are confronted with routes leading to diverse goals, but as I see it, there is

only one road that I can safely recommend for us to tread, and it is the road

to self-determination for the Ibo within the framework of a federated

commonwealth of Nigeria and the Cameroons, leading to a United States of

Africa. Other roads, in my opinion, are calculated to lead us astray from the

path of national self-realization.

It would appear that God has specially created the Ibo people to suffer persecution and be victimized because of their resolute will to live. Since suffering is the label of our tribe, we can afford to be sacrificed for the ultimate redemption of the children of Africa. Is it not fortunate that the Ibo are among the few remnants of indigenous African nations who are still not spoliated by the artificial niceties of Western materialism? Is it not historically significant that throughout the glorious history of Africa, the Ibo is one of the select few to have escaped the humiliation of a conqueror’s sword or to be a victim of a Carthaginian treaty? Search through the records of African history and you will fail to find an occasion when, in any pitched battle, any African nation has either marched across Ibo territory or subjected the Ibo nation to a humiliating conquest. Instead, there is record to show that the martial prowess of the Ibo, at all stages of human history, has rivaled them not only to survive persecution, but also to adapt themselves to the role thus thrust upon them by history, of preserving all that is best and most noble in African culture and tradition. Placed in this high estate, the Ibo cannot shirk the responsibility conferred on it by its manifest destiny. Having undergone a course of suffering the Ibo must therefore enter into its heritage by asserting its birthright, without apologies.

Follow me in a kaleidoscopic study of the Ibo. Four million strong in man-power! Our agricultural resources include economic and food crops which are the bases of modern civilization, not to mention fruits and vegetables which flourish in the tropics! Our mineral resources include coal, lignite, lead, antimony, iron, diatomite, clay, oil, tin! Our forest products include timber of economic value, including iroko and mahogany! Our fauna and flora are marvels of the world! Our land is blessed by waterways of world renown, including the River Niger, Imo River, Cross River! Our ports are among the best known in the continent of Africa. Yet in spite of these natural advantages, which illustrate without doubt the potential wealth of the Ibo, we are among the least developed in Nigeria, economically, and we are so ostracized socially, that we have become extraneous in the political institutions of Nigeria.

I have not come here today in order to catalogue the disabilities which the Ibo suffer, in spite of our potential wealth, in spite of our teeming man-power, in spite of our vitality as an indigenous African people; suffice it to say that it would enable you to appreciate the manifest destiny of the Ibo if I enumerated some of the acts of discrimination against us as a people. Socially, the British Press has not been sparing in describing us as ‘the most hated in Nigeria’. In this unholy crusade, the Daily Mirror, The Times, The Economist, News Review and the Daily Mail have been in the forefront. In the Nigerian Press, you are living witnesses of what has happened in the last eighteen months, when Lagos, Zaria and Calabar sections of the Nigerian Press were virtually encouraged to provoke us to tendentious propaganda. It is needless for me to tell you that today, both in England and in West Africa, the expression ‘Ibo’ has become a word of opprobrium.

Politically, you have seen with your own eyes how four million people were disenfranchized by the British, for decades, because of our alleged backwardness. We have never been represented on the Executive Council, and not one Ibo town has had the franchise, despite the fact that our native political institutions are essentially democratic—in fact, more democratic than any other nation in Africa, in spite of our extreme individualism.

Economically, we have laboured under onerous taxation measures, without receiving sufficient social amenities to justify them. We have been taxed without representation, and our contributions in taxes have been used to develop other areas, Out of proportion to the incidence of taxation in those areas. It would seem that we are becoming a victim of economic annihilation through a gradual but studied process. What are my reasons for cataloguing these disabilities and interpreting them as calculated to emasculate us, and so render us impotent to assert our right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness?

I shall now

state the facts which should be well known to any honest student of Nigerian

history. On the social plane, it will be found that outside of Government

College at Umauhia, there is no other secondary school run by the British

Government in Nigeria in Ibo-land. There is not one secondary school for girls

run by the British Government in our part of the country. In the Northern and

Western Provinces, the contrary is the case. If a survey of the hospital

facilities in Ibo-land were made, embarrassing results might show some sort of

discrimination. Outside of Port Harcourt, fire protection is not provided in

any Ibo town. And yet we have been under the protection of Great Britain for

many decades!

I shall now

state the facts which should be well known to any honest student of Nigerian

history. On the social plane, it will be found that outside of Government

College at Umauhia, there is no other secondary school run by the British

Government in Nigeria in Ibo-land. There is not one secondary school for girls

run by the British Government in our part of the country. In the Northern and

Western Provinces, the contrary is the case. If a survey of the hospital

facilities in Ibo-land were made, embarrassing results might show some sort of

discrimination. Outside of Port Harcourt, fire protection is not provided in

any Ibo town. And yet we have been under the protection of Great Britain for

many decades!

On the economic plane, I cannot

sufficiently impress you because you are too familiar with the victimization

which is our fate. Look at our roads; how many of them are tarred, compared,

for example, with the roads in other parts of the country? Those of you who

have travelled to this assembly by road are witnesses of the corrugated and

utterly unworthy state of the roads which traverse Ibo-land, in spite of the

fact that four million Ibo people pay taxes in order, among others, to have

good roads. With roads must be considered the system of communications, water

and electricity supplies. How many of our towns, for example, have complete

postal, telegraph, telephone and wireless services, compared to towns in other

areas of Nigeria? How many have pipe-borne water supplies? How many have

electricity undertakings? Does not the Ibo tax-payer fulfill his civic duty?

Why, then, must he be a victim of studied official victimization?

Today, these disabilities have been

intensified. There is a movement to disregard traditional organization in the

Ibo nation by the introduction of a specious system of a form of local

government. The placing of the Ibo nation in an artificial regionalization

scheme has left an unfair impression of attempted domination by minorities of

the Ibo people. In the House of Assembly and the Legislative Council the

electoral college system has aided in the complete disenfranchisement of the

Ibo. As a climax, spurious leadership is being foisted upon us—a mis-leadership

which receives official recognition, thus stultifying the legitimate

aspirations of the Ibo. This leadership shows a palpable disloyalty to the Ibo

and loyalty to an alien protecting power.

The only worthwhile stand we can

make as a nation is to assert our right to self-determination, as a unit of a

prospective Federal Commonwealth of Nigeria and the Cameroons, where our rights

will be respected and safeguarded. Roughly speaking, there are twenty main

dialectal regions in the Ibo nation, which can be conveniently departmentalized

as Provinces of an Ibo State, to wit: Mbamili in the northwest, Aniocha in the

west, Anidinma and Ukwuani in the southeast, Nsukka and Udi in the north, Awgu,

Awka and Onitsha in the centre, Ogbaru in the south, Abakaliki and Afikpo in

the northwest, Okigwi, Orlu, Owerri and Mbaise in the east, Ngwa, Bende,

Abiriba Ohafia and Etche in the southwest. These Provinces can have their territorial

boundaries delimited, they can select their capitals, and then can conveniently

develop their resources both for their common benefit and for those of the

other nationalities who make up this great country called Nigeria and the

Cameroons.

|

| Queen Elizabeth and her husband Prince Phillip pictured with Nigeria's first head of state Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe and HRH Obi Okosi, the Obi of Onitsha in the |

The keynote in this address is self-determination for the Ibo. Let us establish

an Ibo State, based on linguistic and ethnic factors, enabling us to take our

place side by side with the other linguistic and ethnic groups which make up

Nigeria and the Cameroons. With the Hausa, Fulani, Kanuri, Yoruba, Ibibio

(Iboku), Angus (Bi-Rom), Tiv, Ijaw, Edo, Urhobo, ltsekiri, Nupe, Igalla, Ogaja,

Gwari, Duala, Bali and other nationalities asserting their right to

self-determination each as separate as the fingers, but united with others as a

part of the same hand, we can reclaim Nigeria and the Cameroons from this

degradation which it has pleased the forces of European imperialism to impose

upon us. Therefore, our meeting today is of momentous importance in the history

of the Ibo, in that opportunity has been presented to us to heed the call of a

despoiled race, to answer the summons to redeem a ravished continent, to rally

forces to the defence of a humiliated country, and to arouse national

consciousness in a demoralized but dynamic nation.

|

Sources:

Nnamdi Azikiwe, Zik: A Selection from the Speeches of Nnamdi Azikiwe, Governor-General of the Federation of Nigeria formerly President of the Nigerian Senate formerly Premier of the Eastern Region of Nigeria (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1961).

Nnamdi Azikiwe, Zik: A Selection from the Speeches of Nnamdi Azikiwe, Governor-General of the Federation of Nigeria formerly President of the Nigerian Senate formerly Premier of the Eastern Region of Nigeria (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1961).

n

Biafran Colt of Arm

Biafra (old eastern Nigeria) adopted

a new flag, national anthem and Odumegwu Ojukwu was promoted to a General and

Head of State.

Biafran Gunner Wings

Biafra On Her 2nd Anniversary 1969

Biafran Rank Insignia

Biafran Scarf for officers

Biafrans Stamp

Biafran tie over 40 years old, testimony of ingenuity of its designers

The Hat Philip Efiong wore as a Major General in Biafra Army- Biafran number 2nd man.

Biafran Gunner wing

Biafran Pilot Gunner Wing

Biafra Air Force Wing

General C. O. Ojukwu Lauching Biafran stamp and pounds

The Burial of Major Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu, August 1967

@ @ @ @ @ @ @

The children of the Most High Aba will never forget 30 May 2015 the heroes day

0 Archives, Articles 03:14

Who said it was only 3 million that came out? The children of the Most High from all corners of Biafraland and beyond. Aba will never forget 30 May 2015. Our departed heroes today are proud of their children because Biafra is here. We get Biafra or we die getting Biafra. One of the two MUST happen.

|

| Biafran Colt of Arm |

|

Biafra (old eastern Nigeria) adopted

a new flag, national anthem and Odumegwu Ojukwu was promoted to a General and

Head of State.

|

Biafran Gunner Wings

|

| Biafra On Her 2nd Anniversary 1969 |

|

| Biafran Rank Insignia |

|

| Biafran Scarf for officers |

|

| Biafrans Stamp |

|

| Biafran tie over 40 years old, testimony of ingenuity of its designers |

|

| The Hat Philip Efiong wore as a Major General in Biafra Army- Biafran number 2nd man. |

|

| Biafran Gunner wing |

|

| Biafran Pilot Gunner Wing |

|

| Biafra Air Force Wing |

|

| General C. O. Ojukwu Lauching Biafran stamp and pounds |

|

| The Burial of Major Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu, August 1967 |

@ @ @ @ @ @ @

The children of the Most High Aba will never forget 30 May 2015 the heroes day

0 Archives, Articles 03:14

Who said it was only 3 million that came out? The children of the Most High from all corners of Biafraland and beyond. Aba will never forget 30 May 2015. Our departed heroes today are proud of their children because Biafra is here. We get Biafra or we die getting Biafra. One of the two MUST happen.

0 Archives, Articles 03:14

Who said it was only 3 million that came out? The children of the Most High from all corners of Biafraland and beyond. Aba will never forget 30 May 2015. Our departed heroes today are proud of their children because Biafra is here. We get Biafra or we die getting Biafra. One of the two MUST happen.

No comments:

Post a Comment